Posted Thursday, 19 February 2026

Scitech sparks science fun in the Wheatbelt

Scitech is travelling 3,000 kilometres throughout the Wheatbelt to bring fun science experiences to 17 schools.

Scitech's Emily Grainger discusses the increase in media on the benefits of explicit teaching and argues that while it's an important asset in a teacher's toolkit, it's not the only way to teach maths.

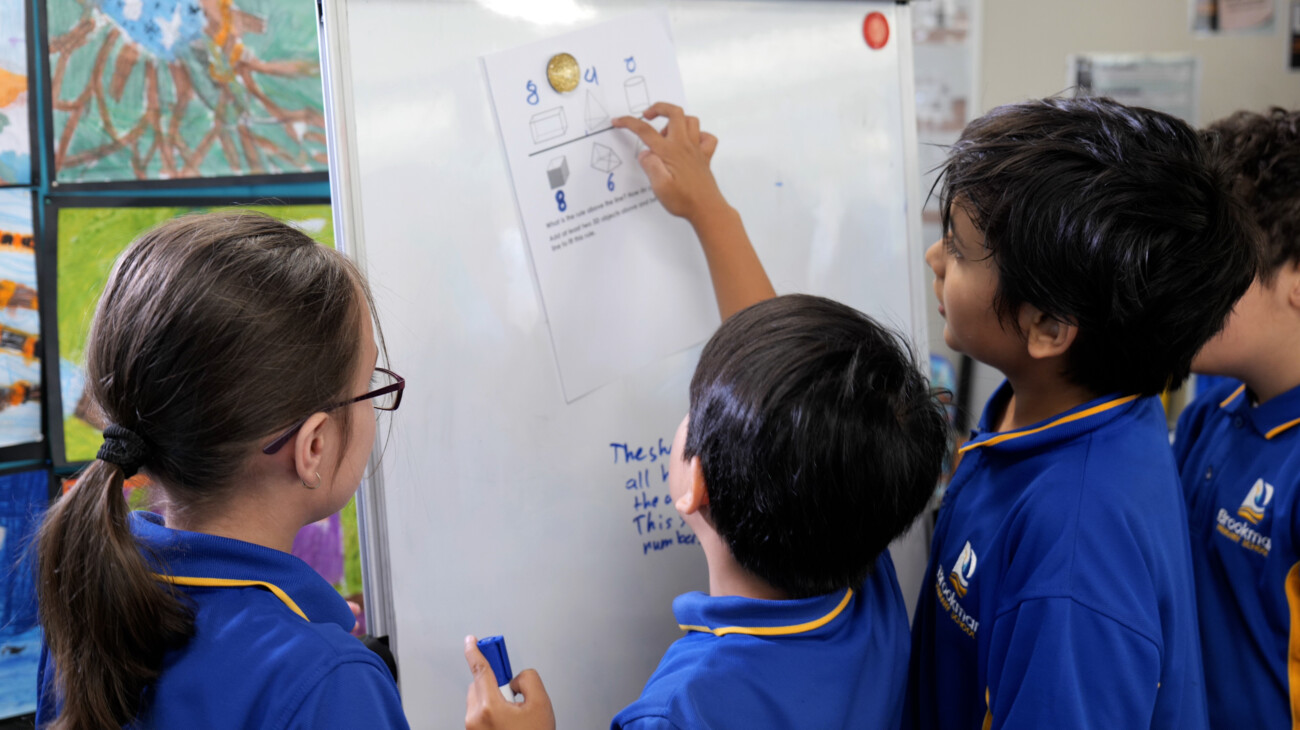

Students apply maths knowledge to a group challenge.

NAPLAN results have landed, showing that 38.5 per cent of Western Australian students in Year 3, and 30.9 per cent of students in Year 5, either need additional support or are still developing their maths skills.

The results follow on from the Grattan Institute’s report The Maths Guarantee: How to boost students’ learning in primary school. Released in April, the report attributed Australia’s maths problem to ‘faddish’ teaching practices, a lack of teacher confidence and directed teachers to use explicit teaching methods.

In response, there’s been a rising trend in media on the benefits of explicit teaching – a back-to-basics approach where teachers clearly show students what to do and how to do it. This approach is great for introducing new concepts and grounding foundational knowledge to memory. And while, explicit teaching is an important asset in a teacher’s toolkit, the positioning of this approach as the only way to teach maths is concerning.

Like anything, explicit teaching has its limitations. It doesn’t give students the opportunity to apply what they’ve learnt to solve problems that exist in their world. Without these kinds of challenges, students miss out on developing skills in critical thinking, creativity, problem-solving, collaboration and resilience within the safety of their classroom.

In a maths lesson I recently observed, students were asked to add a series of numbers and find the combination that would achieve the highest total. One of the students asked me “how do I start?” For me, this highlights that if we always tell students what to do, or only teach them steps, how can we expect them to independently approach problems?

Future jobs and life will demand individuals that can adapt to new technologies, solve new problems and discern fake news. If we are too narrow in our approach to teaching, we will produce students who are good at taking standardised tests but not prepared for a rapidly evolving world.

By focusing on one way of highly structured teaching, we are robbing students of many of the joys of learning – indulging curiosity, having fun, and relating to the world around them. If students don’t understand the relevance of why they’re learning maths, they can become disengaged – the last thing we want to happen in primary school.

A narrow view to teaching also takes away teachers’ professional agency. If we want to lift maths outcomes while also nurturing confident, capable learners, we must empower teachers to use the full spectrum of teaching tools. That means investing in professional development, respecting teacher expertise, and ensuring our education debates reflect the complexity of what it means to teach and learn.

In maths, as in life, success comes not from knowing all the answers, but from knowing how to find them.

Scitech Professional Learning Consultant Emily Grainger.

Upon clicking the "Book Now" or "Buy Gift Card" buttons a new window will open prompting contact information and payment details.